Addressing the mental health crisis requires collaborative, evidence-based solutions that consider local challenges.

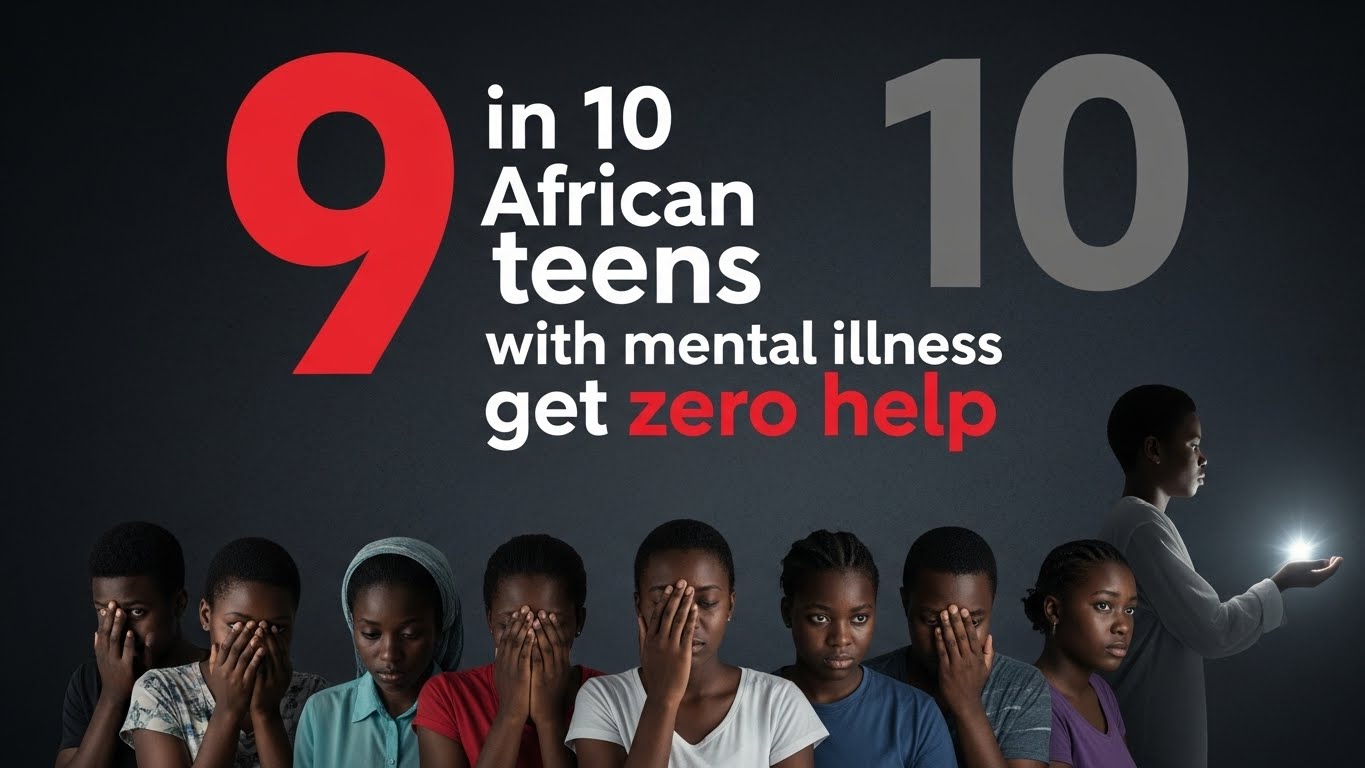

In sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of adolescents suffering from mental health conditions receive no treatment whatsoever, according to new research. Only 10% of the 89 million males and 77 million females facing depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in Sub-Saharan Africa access care. Millions more remain undiagnosed and therefore worse off.

And without support—a crisis is unfolding across the world’s fastest-growing adolescent population and the future of the continent’s progress. With predictions indicating a 130% increase in the burden of mental disorders by 2050, the question isn’t whether we should act, but whether we can afford not to.

“The most vulnerable adolescents are those who remain undiagnosed, those who cannot access mental health care, and those who receive inappropriate or unreliable treatment,” notes authors Claire Hart and Shane A. Norris, in their research title, Adolescent Mental Health in Sub-Saharan Africa: Crisis? What Crisis? Solution? What Solution? , published in January 2025.

The numbers tell a sad story. Adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa experience depression at rates of 27%—more than double the global average of 13%. Anxiety disorders affect 30% compared to 7-10% globally, while post-traumatic stress disorder strikes 21% of young people, seven times higher than the 3-6% seen worldwide.

But statistics alone don’t explain the problem. The root cause lies in systematic neglect: less than 1% of annual health budgets are allocated to mental health, and 40% of African countries lack any dedicated mental health budget. Of 48 sub-Saharan African nations, only three have standalone adolescent mental health policies. There are fewer than 2 mental health workers for every 100,000 people in Africa, leaving overburdened primary care workers with minimal mental health training to fill the gap.

A UNICEF South Africa U-Report Poll on youth mental health showed that 60% of youth needing mental health support didn’t know where to get help. Add pervasive stigma, poverty, food insecurity, and exposure to violence, and you have a generation slipping through the cracks.

What this means

Untreated adolescents don’t simply “grow out of it.” Mental health conditions show an 80% persistence rate, with symptoms worsening over time. These young people face persistent academic failure, fractured family relationships, and social isolation that follows them into adulthood, making employment and stable relationships nearly impossible.

The physical toll is equally severe: cardiovascular disease, weakened immune function, and dangerous behaviours, including substance abuse and unsafe sexual practices. Most tragically, suicide is an emerging cause of death among adolescents in the region. The most vulnerable remain those who are undiagnosed, cannot access care, or receive inappropriate treatment are condemned to a cycle of suffering that could have been prevented.

Recognising the urgent need to address these barriers and bridge the adolescent mental health treatment gap, researchers Hart and Norris examined community-based solutions across the region. Their work, supported by the South African Medical Research Council and the University of the Witwatersrand, sought to identify effective, affordable interventions that could be implemented in resource-constrained settings.

According to the researchers, solutions lie in co-creation and peer-delivered interventions that engage communities in implementing health services while remaining sensitive to their unique challenges. Building referral networks, improving mental health literacy, and ensuring affordability are key steps. With increased funding, these approaches will reduce stigma, foster acceptance, and ultimately help address the mental health crisis.

“Addressing adolescent mental health in sub-Saharan Africa requires collaborative, evidence-based solutions that consider local challenges,” they note.

Already innovative solutions are taking root. In Tanzania, researchers collaborated directly with adolescents and teachers to create a mental health intervention combining digital mood tracking, group discussions, sports, and art therapy. The results? A 16% increase in emotional literacy, 9% improvement in prosocial behaviours, and a 9.4% reduction in mental health difficulties.

Zimbabwe’s Youth Friendship Bench took a different approach, training peers to deliver mental health support. By creating safe spaces where adolescents could identify problems with someone their own age, the programme achieved significant reductions in depression and anxiety while improving overall quality of life. Participants credited feelings of autonomy, active participation, and positive role modeling for their improved mental health.

South Africa’s HERStory peer groups demonstrated similar success, helping adolescents process emotions and manage stress through peer-designed interventions. The common thread? Community involvement and peer delivery dramatically reduced stigma while increasing accessibility.

“These aren’t just programs—they’re proof that collaborative, evidence-based solutions considering local challenges actually work,” notes recent research published in the Journal of Global Health Reports.

The future

The solution lies in a multi-level approach that brings mental health care directly to communities. Task-sharing models train non-specialist providers to deliver interventions in schools and community settings, making care accessible close to where young people live and study—without dependence on caregiver income or work schedules.

But accessibility alone isn’t enough. Effective interventions must be trauma-informed, culturally sensitive, and built on strong referral networks linking community care to health clinics. Mental health literacy programmes for families, teachers, and peers create supportive environments where seeking help becomes normalised rather than stigmatised.

At the policy level, governments must prioritise what they’ve long ignored. Existing frameworks like the Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents and the Mental Health Gap Action Program provide roadmaps—implementation and funding are what’s missing. Interdisciplinary approaches integrating mental health into broader health, education, and social services can transform isolated interventions into sustainable systems.

Adolescence represents a pivotal intervention period—a window of opportunity to establish healthy mental health pathways that last a lifetime. Miss this window, and society pays the price for generations.

According to the researchers, community-driven approaches offer not just treatment, but empowerment.

“Co-creation and task-sharing approaches, involving communities and adolescents in the design and implementation of interventions, will not only help bridge the treatment gap but also empower adolescents to manage their mental health effectively within their local contexts, fostering resilience and well-being,” noted the researchers.

Reference: Hart, C., & Norris, S. A. (2024). Adolescent mental health in sub-Saharan Africa: crisis? What crisis? Solution? What solution?Glob Health Action, 17(1), 2437883. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2024.2437883